A specially commissioned art essay by art mediator and curator Nora Sternfeld for TextWork TextWork is an online platform of Foundation Ricard that publishes monographic texts by international authors on artists from the French scene.

“A convivial society should be designed to allow all its members the

most autonomous action by means of tools least controlled by others”1.

– Ivan Illich

Ivan Illich imagines another world based on “conviviality” – on the ability to

relate to each other and to things, to build the world with tools and to work

together. Yet we do not live in a convivial society, but in a neoliberal world

that promises fantastic infrastructures, while creating new conditions of

exploitation based on algorithms. In this world we find ourselves increasingly

alone in our increasingly unsafe lives. How can we imagine an alternative

future in this world? Might it help to look at irrepressible relationships – the

relationships we entertain with our tools and with each other in spite of

everything?

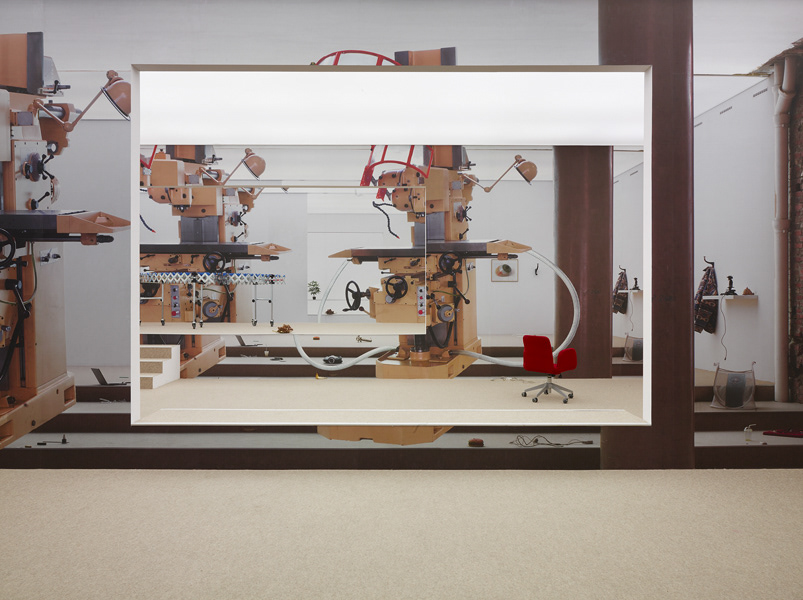

Without naivety or false promises but with persistence, two exhibitions by

Emmanuelle Lainé tackled this question in summer 2017. Where the Rubber

of Ourselves Meets the Road of the Wider World at Palais de Tokyo was a

three-dimensional trompe l’oeil photograph that created a space within the

space by expanding into a walk-in diorama. At first sight, it depicted a

machine – a machine that produces tools. At the same time, Lainé presented

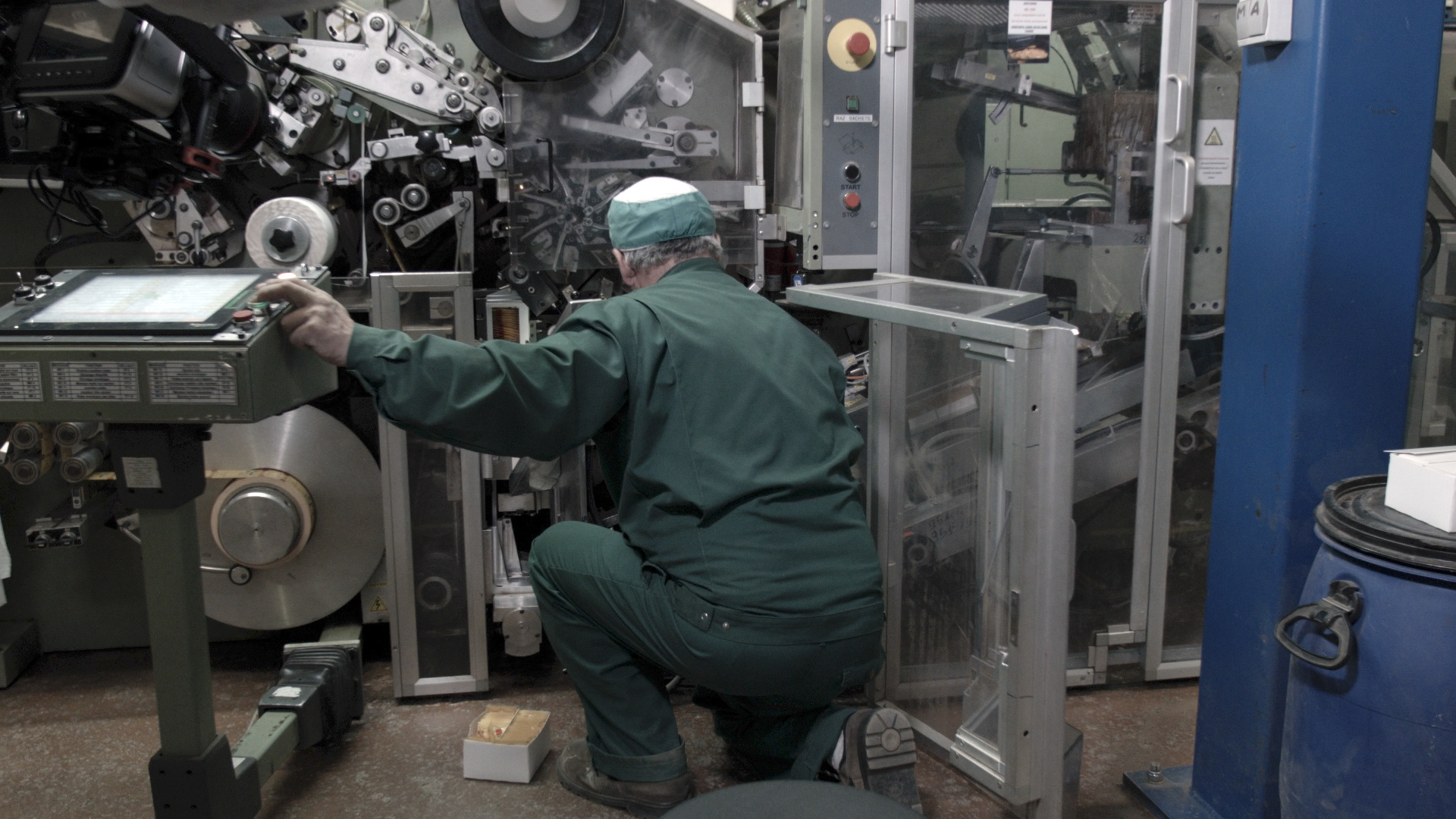

Incremental Self : les corps transparents at Bétonsalon, on the other side of

Paris, a cinematic installation that documents her encounters with three artists

living in a retirement home and a specialised worker – people who entertain a

strong relationship with the tools with which they work. Lainé used two

different artistic approaches to look at our relationship to tools from two

different angles. On the backdrop of the uncanny scenario that characterise

the present world, she revealed to us relationships despite their becoming

impossible in this world: in one case as an encounter with tools, and in the

other as an encounter with those who work in a close relationship with them.

impossible in this world: in one case as an encounter with tools, and in the

other as an encounter with those who work in a close relationship with them.

The work at Palais de Tokyo took the form of a stage inviting

exhibition-goers to step onto it. Those who accepted the enticing invitation to

step into the world of the machine encountered a motley collection of

seemingly abandoned objects, almost ghostly and mute. What could the

empty office furniture, the silent machine, the loose computer cable, the

device for mobile warehouse logistics, the generic image of a seascape and a

rubber hamburger have in common? They formed an abandoned scenario of

everyday activity, instruments, tools and utensils – traces of work. And so,

despite their differences, if not incompatibility, they seemed to point to

something that may yet have to be invented. This is precisely what I want to

address in this essay, which looks for connections by sneaking into the

diorama space at Palais de Tokyo, reading the interviews from the filmic

installation at Bétonsalon, listening to the protagonists and connecting them

to other people, but also inventing things. While most of the protagonists in

this text exist, others are invented, yet they could be real. They are allegories

only in Walter Benjamin’s sense2, in that they maintain a tension between the

personal and the general, the self and the world – a characteristic they share

with the machine and the objects in Lainé’s installation.

So here we are, standing in the middle of a machine – no, in the middle of a

three-dimensional photograph of a machine. The setting simultaneously

reveals and obscures, the materiality of production is at once concrete and generic, specific and universal.

exhibition-goers to step onto it. Those who accepted the enticing invitation to

step into the world of the machine encountered a motley collection of

seemingly abandoned objects, almost ghostly and mute. What could the

empty office furniture, the silent machine, the loose computer cable, the

device for mobile warehouse logistics, the generic image of a seascape and a

rubber hamburger have in common? They formed an abandoned scenario of

everyday activity, instruments, tools and utensils – traces of work. And so,

despite their differences, if not incompatibility, they seemed to point to

something that may yet have to be invented. This is precisely what I want to

address in this essay, which looks for connections by sneaking into the

diorama space at Palais de Tokyo, reading the interviews from the filmic

installation at Bétonsalon, listening to the protagonists and connecting them

to other people, but also inventing things. While most of the protagonists in

this text exist, others are invented, yet they could be real. They are allegories

only in Walter Benjamin’s sense2, in that they maintain a tension between the

personal and the general, the self and the world – a characteristic they share

with the machine and the objects in Lainé’s installation.

So here we are, standing in the middle of a machine – no, in the middle of a

three-dimensional photograph of a machine. The setting simultaneously

reveals and obscures, the materiality of production is at once concrete and generic, specific and universal.

For the history of labour is also the history of

every individual production, a history of exploitation, but also of knowledge

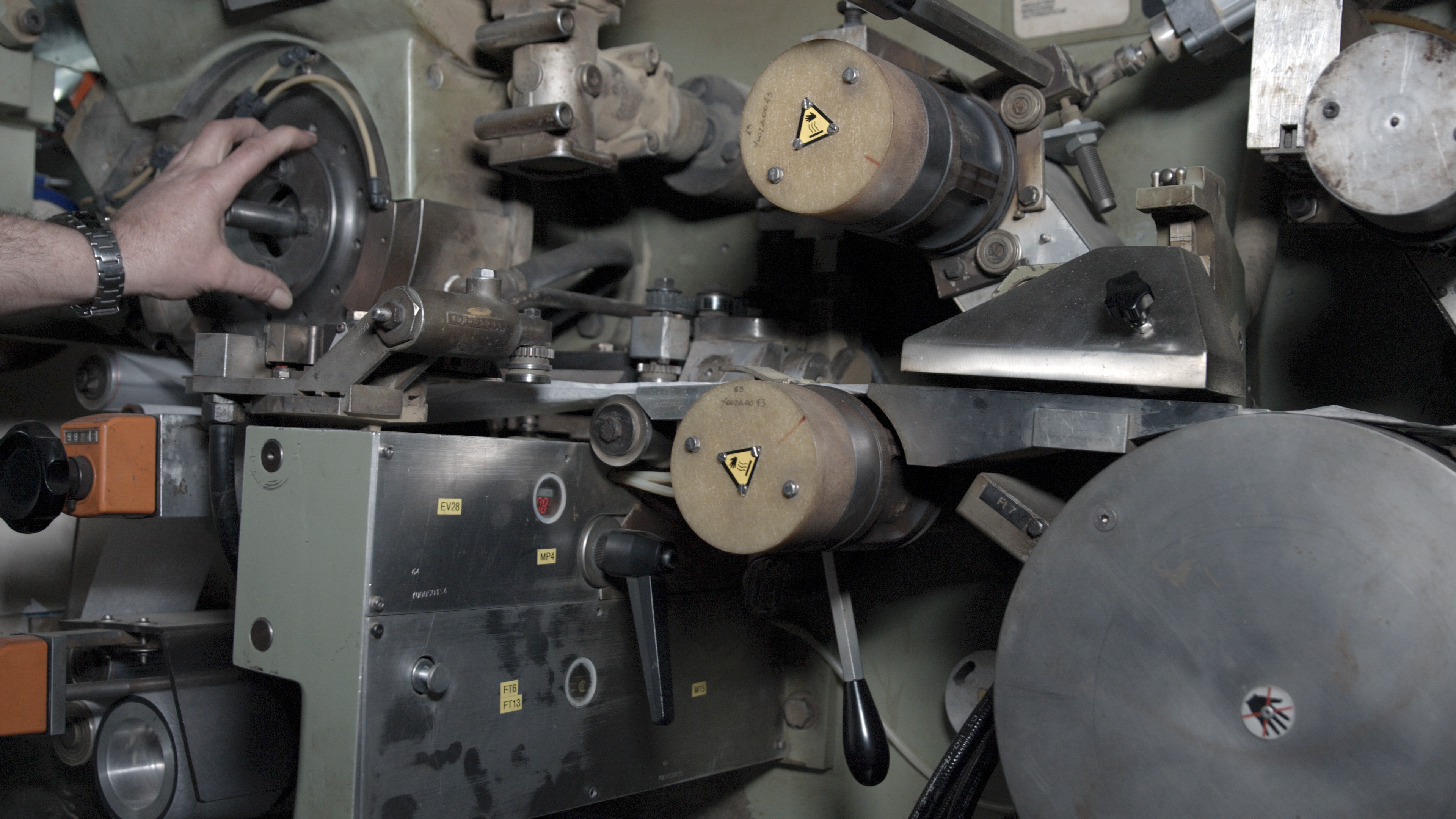

and know-how. With this in mind, let us listen to Thierry Gabrielli, a worker

at Scop-TI, a cooperative factory that produces teas and herbal teas. Lainé

interviewed him near Gémenos, France, in January-February 2017. Here is an

excerpt from the conversation:

every individual production, a history of exploitation, but also of knowledge

and know-how. With this in mind, let us listen to Thierry Gabrielli, a worker

at Scop-TI, a cooperative factory that produces teas and herbal teas. Lainé

interviewed him near Gémenos, France, in January-February 2017. Here is an

excerpt from the conversation:

‘Well, I’m a mechanic by training. We’ve always been told that it took

at least five to eight years to be good at what we do. That’s the time it

takes to get to know these machines. They’re called Teepacks, they’re

German machines – I had to adapt the tools, adapt the machines. […]

We managed to crank up the Teepacks to 186 and even 190 strokes per

minute for the herbal teas. I’m telling you this because in ’89, yes, ’89,

we went on strike in Marseille. When we learned that we would be

relocated, we went on strike. They took our herbal tea bags and sent

them to all the other factories that produced herbal teas, to be packaged

there. This is how they tried to quash the strike. But they didn’t

succeed. These people only made tea! They couldn’t deal with herbal

tea! So some time later, they gave up. Some of our demands were met.

Not all. Transportation allowance and some other things3 . . .’

We thus learn about the specialist skills of Thierry Gabrielli, about his

experience and competence in getting the machine to do something for which

it had not been designed. His work enabled the machine to transcend and

expand its primary function. This had long been useful to the company, and

when the threat of relocation loomed large, it was also useful to the workers

on strike in their negotiations with the management.

experience and competence in getting the machine to do something for which

it had not been designed. His work enabled the machine to transcend and

expand its primary function. This had long been useful to the company, and

when the threat of relocation loomed large, it was also useful to the workers

on strike in their negotiations with the management.

generic, specific and universal. For the history of labour is also the history of

every individual production, a history of exploitation, but also of knowledge

and know-how. With this in mind, let us listen to Thierry Gabrielli, a worker

at Scop-TI, a cooperative factory that produces teas and herbal teas. Lainé

interviewed him near Gémenos, France, in January-February 2017. Here is an

excerpt from the conversation:

‘Well, I’m a mechanic by training. We’ve always been told that it took

at least five to eight years to be good at what we do. That’s the time it

takes to get to know these machines. They’re called Teepacks, they’re

German machines – I had to adapt the tools, adapt the machines. […]

We managed to crank up the Teepacks to 186 and even 190 strokes per

minute for the herbal teas. I’m telling you this because in ’89, yes, ’89,

we went on strike in Marseille. When we learned that we would be

relocated, we went on strike. They took our herbal tea bags and sent

them to all the other factories that produced herbal teas, to be packaged

there. This is how they tried to quash the strike. But they didn’t

succeed. These people only made tea! They couldn’t deal with herbal

tea! So some time later, they gave up. Some of our demands were met.

Not all. Transportation allowance and some other things3 . . .’

We thus learn about the specialist skills of Thierry Gabrielli, about his

experience and competence in getting the machine to do something for which

it had not been designed. His work enabled the machine to transcend and

expand its primary function. This had long been useful to the company, and

when the threat of relocation loomed large, it was also useful to the workers

on strike in their negotiations with the management.

every individual production, a history of exploitation, but also of knowledge

and know-how. With this in mind, let us listen to Thierry Gabrielli, a worker

at Scop-TI, a cooperative factory that produces teas and herbal teas. Lainé

interviewed him near Gémenos, France, in January-February 2017. Here is an

excerpt from the conversation:

‘Well, I’m a mechanic by training. We’ve always been told that it took

at least five to eight years to be good at what we do. That’s the time it

takes to get to know these machines. They’re called Teepacks, they’re

German machines – I had to adapt the tools, adapt the machines. […]

We managed to crank up the Teepacks to 186 and even 190 strokes per

minute for the herbal teas. I’m telling you this because in ’89, yes, ’89,

we went on strike in Marseille. When we learned that we would be

relocated, we went on strike. They took our herbal tea bags and sent

them to all the other factories that produced herbal teas, to be packaged

there. This is how they tried to quash the strike. But they didn’t

succeed. These people only made tea! They couldn’t deal with herbal

tea! So some time later, they gave up. Some of our demands were met.

Not all. Transportation allowance and some other things3 . . .’

We thus learn about the specialist skills of Thierry Gabrielli, about his

experience and competence in getting the machine to do something for which

it had not been designed. His work enabled the machine to transcend and

expand its primary function. This had long been useful to the company, and

when the threat of relocation loomed large, it was also useful to the workers

on strike in their negotiations with the management.

‘We all started new in this warehouse, they call it a “fulfilment centre”.

Only a few people were shifted over from the Leipzig warehouse to get

things running; they had more experience. They trained us. The first

impression was: this place is huge! Having worked on construction

sites before, I thought that this is more like a nursery, in the sense that

they emphasise safety a lot: you have to wear safety boots, high-vis,

use the handrails, don’t take personal belongings down to the

shop-floor and so on. You are supposed to walk on the designated

footpath. They call it “standard work”; everyone is supposed to work in

a similar fashion. It is quite militaristic, in a sense. They actually look

for ex-army men when hiring supervisory staff. Markings on the floor

tell you where to go. For me the easiest way to remember were the

black signs to the smoking area . . . Initially the pressure was not that

high, because the whole warehouse operation had just started and the

majority of people had to get used to things. But after four weeks or so

– I worked in Outbound at the time – it became clear that it’s about

targets, about achieving numbers. More and more people were hired

and I was supposed to train them. That was rather weird for me. They

just called us to Room 175 or something, and when we arrived there

they said: “Oh, great that you have volunteered to become a

‘co-worker’ [trainer]”, though actually we had been informed about

fuck all. Basically they said: “Keep on doing your job, keep smiling

and show the new ones how to work.” Then rumours started to spread:

“Why have these guys been chosen to become ‘co-workers’? Does that

mean they will get a permanent contract?” In this way the first division

amongst the first batch of workers was created. Actually they didn’t

give permanent contracts to all the “co-workers”. I guess I only got one

because I hadn’t taken any sick leave and sometimes came in for extra

shifts5.’

Only a few people were shifted over from the Leipzig warehouse to get

things running; they had more experience. They trained us. The first

impression was: this place is huge! Having worked on construction

sites before, I thought that this is more like a nursery, in the sense that

they emphasise safety a lot: you have to wear safety boots, high-vis,

use the handrails, don’t take personal belongings down to the

shop-floor and so on. You are supposed to walk on the designated

footpath. They call it “standard work”; everyone is supposed to work in

a similar fashion. It is quite militaristic, in a sense. They actually look

for ex-army men when hiring supervisory staff. Markings on the floor

tell you where to go. For me the easiest way to remember were the

black signs to the smoking area . . . Initially the pressure was not that

high, because the whole warehouse operation had just started and the

majority of people had to get used to things. But after four weeks or so

– I worked in Outbound at the time – it became clear that it’s about

targets, about achieving numbers. More and more people were hired

and I was supposed to train them. That was rather weird for me. They

just called us to Room 175 or something, and when we arrived there

they said: “Oh, great that you have volunteered to become a

‘co-worker’ [trainer]”, though actually we had been informed about

fuck all. Basically they said: “Keep on doing your job, keep smiling

and show the new ones how to work.” Then rumours started to spread:

“Why have these guys been chosen to become ‘co-workers’? Does that

mean they will get a permanent contract?” In this way the first division

amongst the first batch of workers was created. Actually they didn’t

give permanent contracts to all the “co-workers”. I guess I only got one

because I hadn’t taken any sick leave and sometimes came in for extra

shifts5.’

Vanda T. could have been anyone. It could have been a mechanic from the

so-called ‘Dock’ who had previously worked in a metal factory at Amazon in

Pozna?, for example. Their experiences would have been similar, as he also

spoke of the permanent feeling of insecurity and of the support among

colleagues that kept him going after all:

so-called ‘Dock’ who had previously worked in a metal factory at Amazon in

Pozna?, for example. Their experiences would have been similar, as he also

spoke of the permanent feeling of insecurity and of the support among

colleagues that kept him going after all:

“During the last few months I realised how insecure the future is –

people came and left again, no one knew who would stay and why. We

are always facing up to this fear – we don’t get any messages saying

that we do a good job and that our job is secure. Despite working hard

they can say “Thank you, there is the door” at any time. And the chaos

concerning payments and bonuses! What do I like here? Most of all,

the good colleagues in the “Dock”6!’

Arlette Chapius, on the other hand, is a retired artist who lives in the Maison

Nationale des Artistes, a French retirement home for artists. When Lainé

interviewed her, she spoke of her relationship to tools:

Nationale des Artistes, a French retirement home for artists. When Lainé

interviewed her, she spoke of her relationship to tools:

‘Tools? Which tools I prefer, you mean? The brushes? Yes. Are there

some brushes that I like more than others? Yes. Well, there are some

right here. This big brush, for example, it’s a beautiful brush, it’s made

of marten fur, it’s worth a fortune now. And I like it very much. It has

been used a lot, it has worked a lot, it’s been . . . I respect it, I really do.

The other ones too, but this one has its very own character. It’s crazy.

Not just physically, but it speaks to me, you see. That’s just how it is.

It’s a pretty extraordinary being, really. Interesting, curious about

everything, I was never bored with it even for a second. I was never

bored. There was always something lively, something new. We don’t

talk to say nothing. On the contrary. And so I liked it very much7.’

some brushes that I like more than others? Yes. Well, there are some

right here. This big brush, for example, it’s a beautiful brush, it’s made

of marten fur, it’s worth a fortune now. And I like it very much. It has

been used a lot, it has worked a lot, it’s been . . . I respect it, I really do.

The other ones too, but this one has its very own character. It’s crazy.

Not just physically, but it speaks to me, you see. That’s just how it is.

It’s a pretty extraordinary being, really. Interesting, curious about

everything, I was never bored with it even for a second. I was never

bored. There was always something lively, something new. We don’t

talk to say nothing. On the contrary. And so I liked it very much7.’

Emmanuelle Lainé, Incremantal Self: Les corps transparents, 2017, exhibition view, Bétonsalon, Paris.

Maybe it is precisely because of the strange feeling of emptiness

characterising Lainé’s installation at Palais de Tokyo with its generic work

furniture that our affective relation to tools, the love and tenderness we

experience for the objects that we manipulate to produce something, can

shine through. What dreams has this office chair been privy to? What

meetings were held at this table, how many trainees’ tears had to be dried

here? Maybe the furniture belongs to an art institution, with its precarious

working conditions. Maybe an unpaid trainee sat here, a young art historian

with ambitious goals and full of shame after being once again humiliated by

the director, who can never remember their name. And what about the rubber

hamburger? What is it doing here? The protagonist that I imagine when I

look at it reckons that housework is not actual work. And yet, as she spends

her time looking after her kids, tidying up the house, trying to get the next

job, building a new website, storing away the rubber hamburger and fishing

characterising Lainé’s installation at Palais de Tokyo with its generic work

furniture that our affective relation to tools, the love and tenderness we

experience for the objects that we manipulate to produce something, can

shine through. What dreams has this office chair been privy to? What

meetings were held at this table, how many trainees’ tears had to be dried

here? Maybe the furniture belongs to an art institution, with its precarious

working conditions. Maybe an unpaid trainee sat here, a young art historian

with ambitious goals and full of shame after being once again humiliated by

the director, who can never remember their name. And what about the rubber

hamburger? What is it doing here? The protagonist that I imagine when I

look at it reckons that housework is not actual work. And yet, as she spends

her time looking after her kids, tidying up the house, trying to get the next

job, building a new website, storing away the rubber hamburger and fishing

her mobile phone out of the loo, she says to herself:

‘This is my work. This is

how I spend my days.’

how I spend my days.’

Lainé’s installations confront us with orphaned objects. Her objects are not

symbols; they bear the traces of real work. Yet in her installations, they are

eerily quiet. Far from the ‘agency’ of things described by Bruno Latour8, they

are hardly compelling and active. Rather, their muteness throws us back onto

our knowledge, the science with which we get them to run, or onto our

experience, with which we can order and store them away in the background.

But if they are not symbols, what are they? Maybe allegories in the

Benjaminian sense – fragments, contemporary ruins that have been removed

from the all-encompassing context of life? Maybe as allegories they stand as

much for themselves as for anything else? Lainé’s installation is not about

work in a post-Fordist age – it is about nothing. It draws us into a space of

silent objects, into an encounter with deceptively perfect settings, with

broken and fragmented tools, in which we might recognise our own

experiences with neoliberal illusions, our own sapience and affects in

post-Fordism – our specific knowledge, our concrete relationships to and

with objects. Because it avoids the totalising reference of the symbol,

allegory partly subverts representation, in the sense of a meaningful

visualisation. The allegorical thinker ‘accepts things as damaged as they are’,

writes Andreas Greiert on Benjamin’s allegorical perspective9. Allegory,

therefore, challenges our thinking – the thinking of a world that is by no

means in order, yet a thinking that is also affective and opens up a possible

other future. Lainé’s installation seems to translate this Benjaminian allegory

of the fragment into the present of post-Fordist or logistics-capitalistic

infrastructures. Maybe the concrete rubber hamburger refers to a counterpart

in our lives; maybe when looking at the simultaneously concrete and generic

– but in any case cheaply framed – images of a horizon over the sea, we

remember exciting moments or the banal emptiness of a waiting room or a

conference hotel.

symbols; they bear the traces of real work. Yet in her installations, they are

eerily quiet. Far from the ‘agency’ of things described by Bruno Latour8, they

are hardly compelling and active. Rather, their muteness throws us back onto

our knowledge, the science with which we get them to run, or onto our

experience, with which we can order and store them away in the background.

But if they are not symbols, what are they? Maybe allegories in the

Benjaminian sense – fragments, contemporary ruins that have been removed

from the all-encompassing context of life? Maybe as allegories they stand as

much for themselves as for anything else? Lainé’s installation is not about

work in a post-Fordist age – it is about nothing. It draws us into a space of

silent objects, into an encounter with deceptively perfect settings, with

broken and fragmented tools, in which we might recognise our own

experiences with neoliberal illusions, our own sapience and affects in

post-Fordism – our specific knowledge, our concrete relationships to and

with objects. Because it avoids the totalising reference of the symbol,

allegory partly subverts representation, in the sense of a meaningful

visualisation. The allegorical thinker ‘accepts things as damaged as they are’,

writes Andreas Greiert on Benjamin’s allegorical perspective9. Allegory,

therefore, challenges our thinking – the thinking of a world that is by no

means in order, yet a thinking that is also affective and opens up a possible

other future. Lainé’s installation seems to translate this Benjaminian allegory

of the fragment into the present of post-Fordist or logistics-capitalistic

infrastructures. Maybe the concrete rubber hamburger refers to a counterpart

in our lives; maybe when looking at the simultaneously concrete and generic

– but in any case cheaply framed – images of a horizon over the sea, we

remember exciting moments or the banal emptiness of a waiting room or a

conference hotel.

Emmanuelle Lainé, Where the Rubber of ourselves Meets the Road of the Wider World, 2017, Palais de Tokyo, Paris.

Maybe we recognise the care of a mother, the attachment of a worker to her colleagues,

colleagues, against whom she is being played off, maybe we know something

about the finesse of machines, about the ability to find our own feelings in

the ghostly world of generic images and to stand by them, to survive, to

produce, to defend ourselves and to continue. These specific relationships to

tools, to things and between humans – which Illich has summed up under the

term ‘conviviality’ – are mostly present in Lainé’s work through their

absence. Lainé’s aesthetics are not relational – or if they are, then only to the

extent that they reveal these relationships. For we may find that her human

diorama of meaningless things refers to ourselves. We encounter the objects

we work with, the means of production that we have long grown used to

investing in ourselves, the loose computer cables, which call upon our

knowledge, our ability to do something else with them than what they were

intended for or what they do to us. Our encounter with objects and tools and

their stories is at once personal and universal. As in Benjamin’s allegory, the

rubber of ourselves meets the road of the wider world.

about the finesse of machines, about the ability to find our own feelings in

the ghostly world of generic images and to stand by them, to survive, to

produce, to defend ourselves and to continue. These specific relationships to

tools, to things and between humans – which Illich has summed up under the

term ‘conviviality’ – are mostly present in Lainé’s work through their

absence. Lainé’s aesthetics are not relational – or if they are, then only to the

extent that they reveal these relationships. For we may find that her human

diorama of meaningless things refers to ourselves. We encounter the objects

we work with, the means of production that we have long grown used to

investing in ourselves, the loose computer cables, which call upon our

knowledge, our ability to do something else with them than what they were

intended for or what they do to us. Our encounter with objects and tools and

their stories is at once personal and universal. As in Benjamin’s allegory, the

rubber of ourselves meets the road of the wider world.

Translated from German by Boris Kremer.

Published in November 2017.

Published in November 2017.

#1 Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality (London: Fontana/Collins, 1975), 33.

#2 Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama [1928], trans. John Osborne, (London – Verso, 2009)

#3 Quoted in Emmanuelle Lainé, Incremental Self (2017), 3-channel video installation, HD video, colour, sound, 20 min.

#4 See ‘Welcome to the Jungle: Working and Struggling in Amazon Warehouses’, AngryWorkersWorld, 20 December

2015, https://angryworkersworld.wordpress.com/2015/12/20/welcome-to-the-jungle-working-and-struggling-in-amazon-warehouses/.

#5 Ibid.

#6 Ibid. For an extensive record of the labour dispute at Amazon in Pozna? in 2015, see Ralf Ruckus, ‘Confronting

Amazon’, Jacobin, 31 March 2016, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/03/amazon-poland-poznan-strikes-workers.‘

#7 Quoted in: Emmanuelle Lainé, Incremental Self (2017) 20 Min, 3 channels installation , H.D. colour and sound video.

#8 See Bruno Latour, ‘The Berlin Key or How to Do Things with Words’, in Matter, Materiality and Modern Culture, ed. P.

M. Graves-Brown (London – Routledge, 2000), 10–21.

#9 Andreas Greiert, Erlösung der Geschichte vom Darstellenden. Grundlagen des Geschichtsdenkens bei Walter Benjamin

1915–1925 (Paderborn – Wilhelm Fink, 2011), 241.

#1de Ivan Illich, Selbstbegrenzung: Eine politisch Kritik der Technik, übers. v. Ylva Eriksson-Kuchenbuch, C. H. Beck,

München 1998, S. 28

#2de Vgl. Walter Benjamin, „Ursprung des deutschen Trauerspiels“, in: Gesammelte Schriften, Bd. I-1, Suhrkamp,

Frankfurt am Main 1987, S. 337-409.

#3de Zit. in: Emmanuelle Lainé, Incremental Self (2017), Drei-Kanal-Videoinstallation, HD-Video, Farbe, Ton, 20 Min.

#4de Siehe „Welcome to the Jungle: Working and Struggling in Amazon Warehouses“, AngryWorkersWorld, 20.12.2015, https://angryworkersworld

#2 Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama [1928], trans. John Osborne, (London – Verso, 2009)

#3 Quoted in Emmanuelle Lainé, Incremental Self (2017), 3-channel video installation, HD video, colour, sound, 20 min.

#4 See ‘Welcome to the Jungle: Working and Struggling in Amazon Warehouses’, AngryWorkersWorld, 20 December

2015, https://angryworkersworld.wordpress.com/2015/12/20/welcome-to-the-jungle-working-and-struggling-in-amazon-warehouses/.

#5 Ibid.

#6 Ibid. For an extensive record of the labour dispute at Amazon in Pozna? in 2015, see Ralf Ruckus, ‘Confronting

Amazon’, Jacobin, 31 March 2016, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/03/amazon-poland-poznan-strikes-workers.‘

#7 Quoted in: Emmanuelle Lainé, Incremental Self (2017) 20 Min, 3 channels installation , H.D. colour and sound video.

#8 See Bruno Latour, ‘The Berlin Key or How to Do Things with Words’, in Matter, Materiality and Modern Culture, ed. P.

M. Graves-Brown (London – Routledge, 2000), 10–21.

#9 Andreas Greiert, Erlösung der Geschichte vom Darstellenden. Grundlagen des Geschichtsdenkens bei Walter Benjamin

1915–1925 (Paderborn – Wilhelm Fink, 2011), 241.

#1de Ivan Illich, Selbstbegrenzung: Eine politisch Kritik der Technik, übers. v. Ylva Eriksson-Kuchenbuch, C. H. Beck,

München 1998, S. 28

#2de Vgl. Walter Benjamin, „Ursprung des deutschen Trauerspiels“, in: Gesammelte Schriften, Bd. I-1, Suhrkamp,

Frankfurt am Main 1987, S. 337-409.

#3de Zit. in: Emmanuelle Lainé, Incremental Self (2017), Drei-Kanal-Videoinstallation, HD-Video, Farbe, Ton, 20 Min.

#4de Siehe „Welcome to the Jungle: Working and Struggling in Amazon Warehouses“, AngryWorkersWorld, 20.12.2015, https://angryworkersworld

Nora Sternfeld is an art mediator and curator. She is professor for art education at the HFBK Hamburg. In addition, she is co-director of the /ecm - Master Course for Exhibition Theory and Practice at the University of Applied Arts Vienna, in the core team of schnittpunkt. austellungstheorie & praxis, co-founder and partner of trafo.K, Office for Education, Art and Critical Knowledge Production (Vienna) and since 2011 part of freethought, Platform for Research, Education and Production (London). In this context she was also one of the artistic directors* of the Bergen Assembly 2016 and is 2020 BAK Fellow, basis voor actuele kunst (Utrecht). She publishes on contemporary art, educational theory, exhibitions, historical politics and anti-racism.